Israeli legislation ostensibly intended to tackle noise pollution from Muslim houses of worship has, paradoxically, served chiefly to provoke a cacophony of indignation across much of the Middle East.

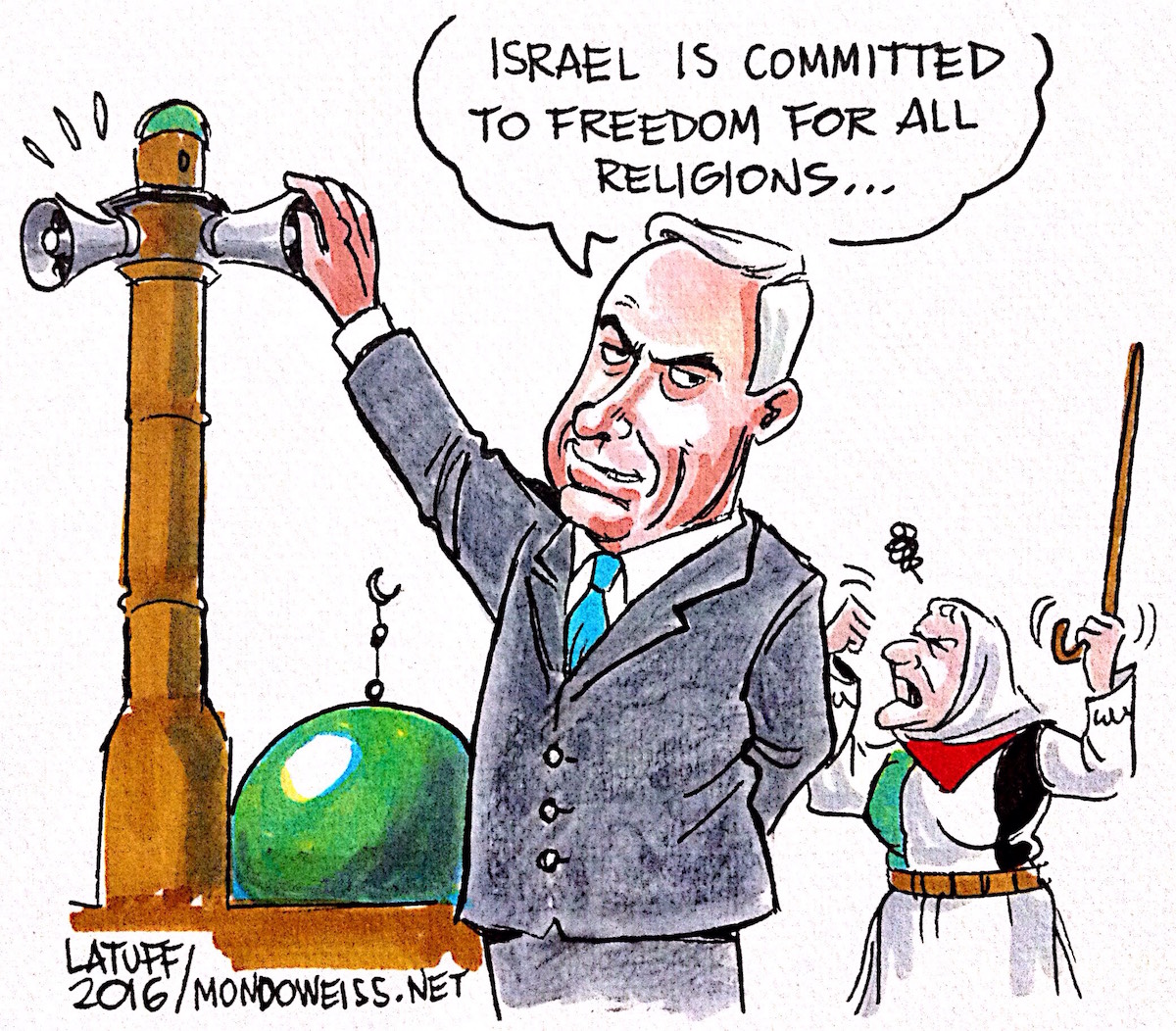

Image Credit: Carlos Latuff/Mondoweiss

Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared his support this month for the so-called “muezzin bill”, claiming it was urgently needed to stop the dawn call to prayer from mosques ruining the Israeli public’s sleep. A vote in the parliament is due this week. The use of loudspeakers by muezzins was unnecessarily disruptive, Mr Netanyahu argued, in an age of alarm clocks and phone apps.

But the one in five of Israel’s population who are Palestinian, most of them Muslim, and a further 300,000 living under occupation in East Jerusalem, say the legislation is grossly discriminatory. The bill’s environmental rationale is bogus, they note. Moti Yogev, a settler leader who drafted the bill, originally wanted the loudspeaker ban to curb the broadcasting of sermons supposedly full of “incitement” against Israel.

And last week, after the Jewish ultra-Orthodox lobby began to fear the bill might also apply to sirens welcoming in the Sabbath, the government hurriedly introduced an exemption for synagogues.

The “muezzin bill” does not arrive in a politically neutral context. The extremist wing of the settler movement championing it has been vandalizing and torching mosques in Israel and the occupied territories for years.

The new bill follows hot on the heels of a government-sponsored expulsion law that allows Jewish legislators to oust from the parliament the Palestinian minority’s representatives if they voice unpopular views.

Palestinian leaders in Israel are rarely invited on TV, unless it is to defend themselves against accusations of treasonous behavior.

And this month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

Incrementally, Israel’s Palestinian minority has found itself squeezed out of the public sphere. The “muezzin bill” is just the latest step in making them inaudible as well as invisible.

Notably, Basel Ghattas, a Palestinian Christian legislator from the Galilee, denounced the bill too. Churches in Nazareth, Jerusalem, and Haifa, he vowed, would broadcast the muezzin’s call to prayer if mosques were muzzled.

For Ghattas and others, the bill is as much an assault on the community’s beleaguered Palestinian identity as it is on its Muslim character. Netanyahu, on the other hand, has dismissed criticism by comparing the proposed restrictions to measures adopted in countries like France and Switzerland. What is good for Europe, he argues, is good for Israel.

Except Israel, it hardly needs pointing out, is not in Europe. And its Palestinians are the native population, not immigrants.

Haneen Zoabi, another lawmaker, observed that the legislation was not about “the noise in [Israeli Jews’] ears but the noise in their minds”

Haneen Zoabi, another lawmaker, observed that the legislation was not about “the noise in [Israeli Jews’] ears but the noise in their minds”. Their colonial fears, she said, were evoked by the Palestinians’ continuing vibrant presence in Israel – a presence that was supposed to have been extinguished in 1948 with the Nakba, the creation of a Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinians’ homeland.

That point was illustrated inadvertently over the weekend by dozens of fires that ravaged pine forests and neighboring homes across Israel, fuelled by high winds and months of drought.

Some posting on social media relished the fires as God’s punishment for the “muezzin bill”.

With almost as little evidence, Netanyahu accused Palestinians of setting “terrorist” fires to burn down the Israeli state. The Israeli prime minister needs to distract attention from his failure to heed warnings six years ago, when similar blazes struck, that Israel’s densely packed forests pose a fire hazard.

If it turns out that some of the fires were set on purpose, Netanyahu will have no interest in explaining why.

Many of the forests were planted decades ago by Israel to conceal the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, after 80 percent of the Palestinian population – some 750,000 – were expelled outside Israel’s new borders in 1948. Today they live in refugee camps, including in the West Bank and Gaza.

According to Israeli scholars, the country’s European founders turned the pine tree into a “weapon of war”, using it to erase any trace of the Palestinians. The Israeli historian Ilan Pappe calls this policy “memoricide”.

Olive trees and other native species like carob, pomegranate and citrus were also uprooted in favor of the pine. Importing the landscape of Europe was a way to ensure Jewish immigrants would not feel homesick.

Today, for many Israeli Jews, only the muezzin threatens this contrived idyll. His intermittent call to prayer emanates from the dozens of Palestinian communities that survived 1948’s mass expulsions and were not replaced with pine trees.

Like an unwelcome ghost, the sound now haunts neighboring Jewish towns.

The “muezzin bill” aims to eradicate the aural remnants of Palestine as completely as Israel’s forests obliterated its visible parts – and reassure Israelis that they live in Europe rather than the Middle East.

The “muezzin bill” aims to eradicate the aural remnants of Palestine as completely as Israel’s forests obliterated its visible parts – and reassure Israelis that they live in Europe rather than the Middle East.

Israeli legislation ostensibly intended to tackle noise pollution from Muslim houses of worship has, paradoxically, served chiefly to provoke a cacophony of indignation across much of the Middle East.

Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared his support this month for the so-called “muezzin bill”, claiming it was urgently needed to stop the dawn call to prayer from mosques ruining the Israeli public’s sleep. A vote in the parliament is due this week. The use of loudspeakers by muezzins was unnecessarily disruptive, Mr Netanyahu argued, in an age of alarm clocks and phone apps.

But the one in five of Israel’s population who are Palestinian, most of them Muslim, and a further 300,000 living under occupation in East Jerusalem, say the legislation is grossly discriminatory. The bill’s environmental rationale is bogus, they note. Moti Yogev, a settler leader who drafted the bill, originally wanted the loudspeaker ban to curb the broadcasting of sermons supposedly full of “incitement” against Israel.

And last week, after the Jewish ultra-Orthodox lobby began to fear the bill might also apply to sirens welcoming in the Sabbath, the government hurriedly introduced an exemption for synagogues.

The “muezzin bill” does not arrive in a politically neutral context. The extremist wing of the settler movement championing it has been vandalizing and torching mosques in Israel and the occupied territories for years.

The new bill follows hot on the heels of a government-sponsored expulsion law that allows Jewish legislators to oust from the parliament the Palestinian minority’s representatives if they voice unpopular views.

Palestinian leaders in Israel are rarely invited on TV, unless it is to defend themselves against accusations of treasonous behavior.

This month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

And this month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

Incrementally, Israel’s Palestinian minority has found itself squeezed out of the public sphere. The “muezzin bill” is just the latest step in making them inaudible as well as invisible.

Notably, Basel Ghattas, a Palestinian Christian legislator from the Galilee, denounced the bill too. Churches in Nazareth, Jerusalem, and Haifa, he vowed, would broadcast the muezzin’s call to prayer if mosques were muzzled.

For Ghattas and others, the bill is as much an assault on the community’s beleaguered Palestinian identity as it is on its Muslim character. Netanyahu, on the other hand, has dismissed criticism by comparing the proposed restrictions to measures adopted in countries like France and Switzerland. What is good for Europe, he argues, is good for Israel.

Except Israel, it hardly needs pointing out, is not in Europe. And its Palestinians are the native population, not immigrants.

Haneen Zoabi, another lawmaker, observed that the legislation was not about “the noise in [Israeli Jews’] ears but the noise in their minds”. Their colonial fears, she said, were evoked by the Palestinians’ continuing vibrant presence in Israel – a presence that was supposed to have been extinguished in 1948 with the Nakba, the creation of a Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinians’ homeland.

That point was illustrated inadvertently over the weekend by dozens of fires that ravaged pine forests and neighboring homes across Israel, fuelled by high winds and months of drought.

Some posting on social media relished the fires as God’s punishment for the “muezzin bill”.

With almost as little evidence, Netanyahu accused Palestinians of setting “terrorist” fires to burn down the Israeli state. The Israeli prime minister needs to distract attention from his failure to heed warnings six years ago, when similar blazes struck, that Israel’s densely packed forests pose a fire hazard.

If it turns out that some of the fires were set on purpose, Netanyahu will have no interest in explaining why.

Many of the forests were planted decades ago by Israel to conceal the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, after 80 percent of the Palestinian population – some 750,000 – were expelled outside Israel’s new borders in 1948. Today they live in refugee camps, including in the West Bank and Gaza.

According to Israeli scholars, the country’s European founders turned the pine tree into a “weapon of war”, using it to erase any trace of the Palestinians. The Israeli historian Ilan Pappe calls this policy “memoricide”.

Olive trees and other native species like carob, pomegranate and citrus were also uprooted in favor of the pine. Importing the landscape of Europe was a way to ensure Jewish immigrants would not feel homesick.

Today, for many Israeli Jews, only the muezzin threatens this contrived idyll. His intermittent call to prayer emanates from the dozens of Palestinian communities that survived 1948’s mass expulsions and were not replaced with pine trees.

Like an unwelcome ghost, the sound now haunts neighboring Jewish towns.

The “muezzin bill” aims to eradicate the aural remnants of Palestine as completely as Israel’s forests obliterated its visible parts – and reassure Israelis that they live in Europe rather than the Middle East.

Israeli legislation ostensibly intended to tackle noise pollution from Muslim houses of worship has, paradoxically, served chiefly to provoke a cacophony of indignation across much of the Middle East.

Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared his support this month for the so-called “muezzin bill”, claiming it was urgently needed to stop the dawn call to prayer from mosques ruining the Israeli public’s sleep. A vote in the parliament is due this week. The use of loudspeakers by muezzins was unnecessarily disruptive, Mr Netanyahu argued, in an age of alarm clocks and phone apps.

But the one in five of Israel’s population who are Palestinian, most of them Muslim, and a further 300,000 living under occupation in East Jerusalem, say the legislation is grossly discriminatory. The bill’s environmental rationale is bogus, they note. Moti Yogev, a settler leader who drafted the bill, originally wanted the loudspeaker ban to curb the broadcasting of sermons supposedly full of “incitement” against Israel.

Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared his support this month for the so-called “muezzin bill”, claiming it was urgently needed to stop the dawn call to prayer from mosques ruining the Israeli public’s sleep. A vote in the parliament is due this week. The use of loudspeakers by muezzins was unnecessarily disruptive, Mr Netanyahu argued, in an age of alarm clocks and phone apps.

But the one in five of Israel’s population who are Palestinian, most of them Muslim, and a further 300,000 living under occupation in East Jerusalem, say the legislation is grossly discriminatory. The bill’s environmental rationale is bogus, they note. Moti Yogev, a settler leader who drafted the bill, originally wanted the loudspeaker ban to curb the broadcasting of sermons supposedly full of “incitement” against Israel.

And last week, after the Jewish ultra-Orthodox lobby began to fear the bill might also apply to sirens welcoming in the Sabbath, the government hurriedly introduced an exemption for synagogues.

The “muezzin bill” does not arrive in a politically neutral context. The extremist wing of the settler movement championing it has been vandalizing and torching mosques in Israel and the occupied territories for years.

The new bill follows hot on the heels of a government-sponsored expulsion law that allows Jewish legislators to oust from the parliament the Palestinian minority’s representatives if they voice unpopular views.

Palestinian leaders in Israel are rarely invited on TV, unless it is to defend themselves against accusations of treasonous behavior.

This month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

And this month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

Incrementally, Israel’s Palestinian minority has found itself squeezed out of the public sphere. The “muezzin bill” is just the latest step in making them inaudible as well as invisible.

Notably, Basel Ghattas, a Palestinian Christian legislator from the Galilee, denounced the bill too. Churches in Nazareth, Jerusalem, and Haifa, he vowed, would broadcast the muezzin’s call to prayer if mosques were muzzled.

For Ghattas and others, the bill is as much an assault on the community’s beleaguered Palestinian identity as it is on its Muslim character. Netanyahu, on the other hand, has dismissed criticism by comparing the proposed restrictions to measures adopted in countries like France and Switzerland. What is good for Europe, he argues, is good for Israel.

Except Israel, it hardly needs pointing out, is not in Europe. And its Palestinians are the native population, not immigrants.

Haneen Zoabi, another lawmaker, observed that the legislation was not about “the noise in [Israeli Jews’] ears but the noise in their minds”. Their colonial fears, she said, were evoked by the Palestinians’ continuing vibrant presence in Israel – a presence that was supposed to have been extinguished in 1948 with the Nakba, the creation of a Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinians’ homeland.

That point was illustrated inadvertently over the weekend by dozens of fires that ravaged pine forests and neighboring homes across Israel, fuelled by high winds and months of drought.

Some posting on social media relished the fires as God’s punishment for the “muezzin bill”.

With almost as little evidence, Netanyahu accused Palestinians of setting “terrorist” fires to burn down the Israeli state. The Israeli prime minister needs to distract attention from his failure to heed warnings six years ago, when similar blazes struck, that Israel’s densely packed forests pose a fire hazard.

If it turns out that some of the fires were set on purpose, Netanyahu will have no interest in explaining why.

Many of the forests were planted decades ago by Israel to conceal the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, after 80 percent of the Palestinian population – some 750,000 – were expelled outside Israel’s new borders in 1948. Today they live in refugee camps, including in the West Bank and Gaza.

According to Israeli scholars, the country’s European founders turned the pine tree into a “weapon of war”, using it to erase any trace of the Palestinians. The Israeli historian Ilan Pappe calls this policy “memoricide”.

Olive trees and other native species like carob, pomegranate and citrus were also uprooted in favor of the pine. Importing the landscape of Europe was a way to ensure Jewish immigrants would not feel homesick.

Today, for many Israeli Jews, only the muezzin threatens this contrived idyll. His intermittent call to prayer emanates from the dozens of Palestinian communities that survived 1948’s mass expulsions and were not replaced with pine trees.

Like an unwelcome ghost, the sound now haunts neighboring Jewish towns.

The “muezzin bill” aims to eradicate the aural remnants of Palestine as completely as Israel’s forests obliterated its visible parts – and reassure Israelis that they live in Europe rather than the Middle East.

Israeli legislation ostensibly intended to tackle noise pollution from Muslim houses of worship has, paradoxically, served chiefly to provoke a cacophony of indignation across much of the Middle East.

Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared his support this month for the so-called “muezzin bill”, claiming it was urgently needed to stop the dawn call to prayer from mosques ruining the Israeli public’s sleep. A vote in the parliament is due this week. The use of loudspeakers by muezzins was unnecessarily disruptive, Mr Netanyahu argued, in an age of alarm clocks and phone apps.

But the one in five of Israel’s population who are Palestinian, most of them Muslim, and a further 300,000 living under occupation in East Jerusalem, say the legislation is grossly discriminatory. The bill’s environmental rationale is bogus, they note. Moti Yogev, a settler leader who drafted the bill, originally wanted the loudspeaker ban to curb the broadcasting of sermons supposedly full of “incitement” against Israel.

And last week, after the Jewish ultra-Orthodox lobby began to fear the bill might also apply to sirens welcoming in the Sabbath, the government hurriedly introduced an exemption for synagogues.

The “muezzin bill” does not arrive in a politically neutral context. The extremist wing of the settler movement championing it has been vandalizing and torching mosques in Israel and the occupied territories for years.

The new bill follows hot on the heels of a government-sponsored expulsion law that allows Jewish legislators to oust from the parliament the Palestinian minority’s representatives if they voice unpopular views.

Palestinian leaders in Israel are rarely invited on TV, unless it is to defend themselves against accusations of treasonous behavior.

And this month a branch of a major restaurant chain in the northern city of Haifa, where many Palestinian citizens live, banned staff from speaking Arabic to avoid Jewish customers’ suspicions that they were being covertly derided.

Incrementally, Israel’s Palestinian minority has found itself squeezed out of the public sphere. The “muezzin bill” is just the latest step in making them inaudible as well as invisible.

Notably, Basel Ghattas, a Palestinian Christian legislator from the Galilee, denounced the bill too. Churches in Nazareth, Jerusalem, and Haifa, he vowed, would broadcast the muezzin’s call to prayer if mosques were muzzled.

For Ghattas and others, the bill is as much an assault on the community’s beleaguered Palestinian identity as it is on its Muslim character. Netanyahu, on the other hand, has dismissed criticism by comparing the proposed restrictions to measures adopted in countries like France and Switzerland. What is good for Europe, he argues, is good for Israel.

Except Israel, it hardly needs pointing out, is not in Europe. And its Palestinians are the native population, not immigrants.

Haneen Zoabi, another lawmaker, observed that the legislation was not about “the noise in [Israeli Jews’] ears but the noise in their minds”. Their colonial fears, she said, were evoked by the Palestinians’ continuing vibrant presence in Israel – a presence that was supposed to have been extinguished in 1948 with the Nakba, the creation of a Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinians’ homeland.

That point was illustrated inadvertently over the weekend by dozens of fires that ravaged pine forests and neighboring homes across Israel, fuelled by high winds and months of drought.

Some posting on social media relished the fires as God’s punishment for the “muezzin bill”.

With almost as little evidence, Netanyahu accused Palestinians of setting “terrorist” fires to burn down the Israeli state. The Israeli prime minister needs to distract attention from his failure to heed warnings six years ago, when similar blazes struck, that Israel’s densely packed forests pose a fire hazard.

If it turns out that some of the fires were set on purpose, Netanyahu will have no interest in explaining why.

Many of the forests were planted decades ago by Israel to conceal the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, after 80 percent of the Palestinian population – some 750,000 – were expelled outside Israel’s new borders in 1948. Today they live in refugee camps, including in the West Bank and Gaza.

According to Israeli scholars, the country’s European founders turned the pine tree into a “weapon of war”, using it to erase any trace of the Palestinians. The Israeli historian Ilan Pappe calls this policy “memoricide”.

Olive trees and other native species like carob, pomegranate and citrus were also uprooted in favor of the pine. Importing the landscape of Europe was a way to ensure Jewish immigrants would not feel homesick.

Today, for many Israeli Jews, only the muezzin threatens this contrived idyll. His intermittent call to prayer emanates from the dozens of Palestinian communities that survived 1948’s mass expulsions and were not replaced with pine trees.

Like an unwelcome ghost, the sound now haunts neighboring Jewish towns.

The “muezzin bill” aims to eradicate the aural remnants of Palestine as completely as Israel’s forests obliterated its visible parts – and reassure Israelis that they live in Europe rather than the Middle East.

(This article first published on Mondoweiss is being republished with permission).