Bombay 1992-1993 and Coimbatore 1997-98 may become permanently etched on the post-1947 canvas of the sub-continent. In a sordid run-on of the saga that preceded Partition and the birth of two nation-states of India and Pakistan, both Bombay and Coimbatore were the locales for unspeakable venom against the minority Muslim community under an avowedly secular state.The pogroms resulted in planned and brutal retaliatory acts of terrorism – serial bomb blasts killing innocent civilians. Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) is believed to have exploited the local alienation, despair and outrage.

For the last 37 years — in 1961, the first post-Partition communal riot erupted in Ranchi, Bihar and took its heavy toll of life and property, even official statistics show the minorities to be the major victims, riot after riot. They also reveal a discernible pattern, blurred and unformed in the initial decades, evolving gradually into a clear-cut design that today has assumed a frightening shape. The pattern reveals a distinctly soft approach by the state and its armed manifestation, the police, towards Hindu communal organisations whose fomenting of communal venom months before the riot actually erupts goes unchecked. Those guilty of instigating acts of violence against the minorities are then shielded so that they go unpunished. In the last 15 years or so, the police have themselves actively participated in riots by aiding the aggressors.

A wider public sanction has granted legitimacy to this treatment of India’s largest minority that stayed on after the division of the sub-continent. This sanction harks back to pre- and post-Partition communal discourse wherein Muslims were dubbed as having extra-territorial loyalties, and being the sole repositories of separatist tendencies.

On the flip side, there are consistent efforts made by sections of the ISI and other outfits in Pakistan (see page 26 of this issue) to reap their narrow and communal gains through a systematic exploitation of the internally generated feelings of alienation.

What are the consequences of this blatant abdication of responsibility of the state? When the minorities conclude through bitter real-life experiences, riot after riot, that they can expect no protection or fair treatment from the custodians of law? When the aggressors — be they individuals from Hindu communal organisations or policemen — go unpunished? When increasing evidence, collected by Indian intelligence agencies since the late eighties, shows an active policy by Pakistan’s ISI to use this internal alienation and despair to promote terrorist acts targeting civilians?

“The alienation of any section of society is a ripe breeding ground for unfortunate, even deplorable methods of retaliation,” said B.G. Deshmukh, former Union cabinet secretary, while speaking to Communalism Combat.

This alienation that has forced sections of the minority to take to terrorism in retaliation has not surfaced overnight. Unless the Indian state heeds the warning signals sent out through the bomb blasts in Bombay and Coimbatore, we may be making society increasingly vulnerable to such violent acts of retaliation.

The build-up to each round of violence unleashed against the minorities over the decades reveals systematic propaganda unleashed by Hindu communal organisations — be it the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (indicted by government-appointed judicial commissions in the Tellicherry, Bhiwandi and Ahmedabad riots), the Jana Sangh (held responsible in Ranchi, Ahmedabad), the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal (in Meerut and Bhagalpur) the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, the Hindu Munnani in Tamil Nadu — to communalise society and wings of the state.

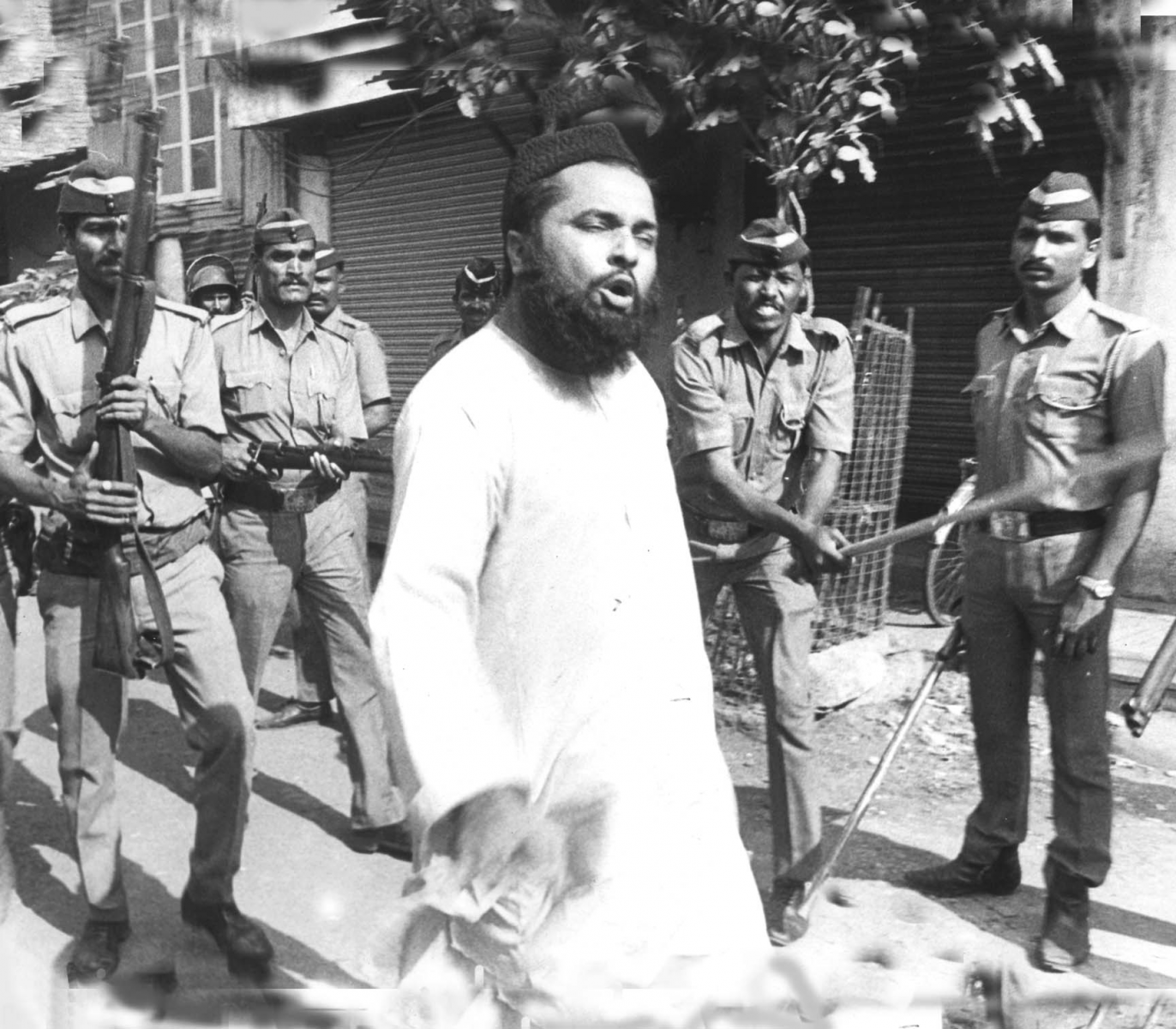

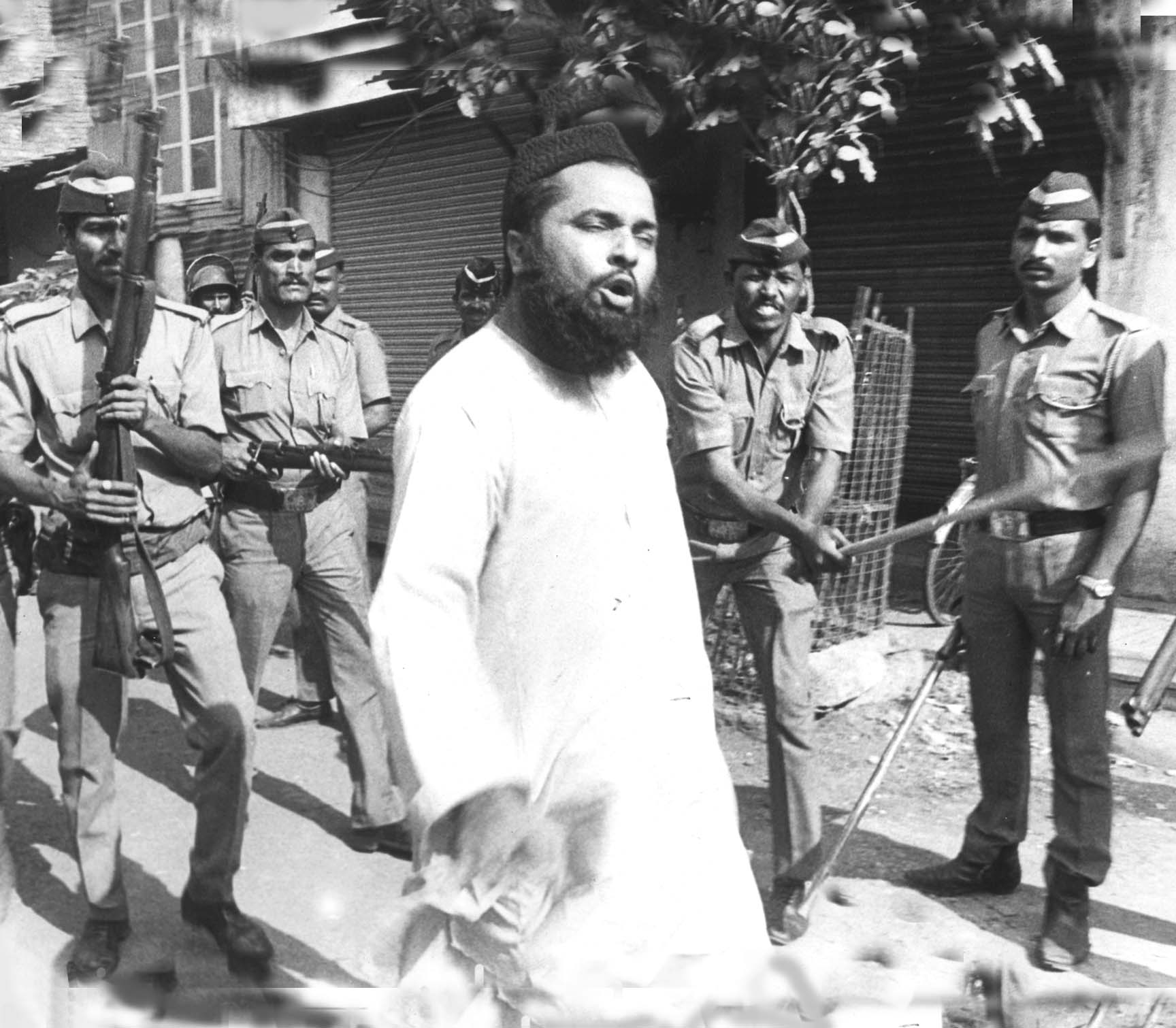

‘I wanted the government to know that if it cannot protect the Muslims of this country, we will protect ourselves’.

-- Dr. Jalees Ansari, during his interrogation after being arrested in Bombay on january 13, 1994, on charges of master-minding at least 40 bomb blasts in various parts of the countrysince 1994.

The carefully-crafted propaganda harps on some common themes to set the stage for communal conflagration. Whether it be the question of Urdu being accepted as a state language in Bihar, or the routes of the Shiv Jayanti, Ram Janmi, Ramjanmabhoomi processions in Bhiwandi-Bombay, Ahmedabad and all over north India, on each occasion these outfits have successfully whipped up communal feelings in the Hindu majority. Speeches of leaders from various outfits, the literature and pamphlets distributed by them in every riot hark back to the theme of Muslims as “anti-national, fanatical and violent.”

In the large majority of post-Partition communal riots, the Muslim minority was victimised and targeted. But in 1984, a brutal anti-Sikh pogrom was launched in the country’s capital following Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination on October 31, 1984 by her Sikh bodyguards. It exposed both Congress(I) politicians who turned a blind eye and allowed the killings to continue over three days and the local police which actively participated in the violence. The Hindu-Christian riots in Kanyakumari in 1982 exposed how the propaganda of Hindu communal organisations also targets the Christian minority as the “alien outsider.”

“In any society, the majority is responsible for exuding a feeling of security in the minority who should feel that they can trust the man in charge of the police force, that they are safe and feel protected by him,” commented Julio Ribeiro, former commissioner of police, Bombay and DGP, Punjab to Communalism Combat. Shankar Sen, a senior IPS officer and presently chairperson of the National Minorities Commission agrees. “It is the responsibility of the majority community to prevent a situation in which the minority community feels beleaguered.”

The former police commissioner of Bombay (1993-1995), Satish Sahney, speaking to CC, said “The sense of alienation that the Muslim minority today experiences, compounded by its low education and professional opportunities must be removed.”

A close scrutiny of all the judicial commissions into post-partition communal riots in India shows how every report presented to the state or central government has indicted the police for its communal bias since 1961. The prejudice reflects itself in a more aggressive treatment of the minority and shielding of the aggressors belonging to Hindu communal organisations through the tailoring or scotching of evidence so that the guilty go scot free.

It started with sporadic riots in the sixties — Ranchi (Bihar), Ahmedabad (Gujarat), Jamshedpur (Bihar), Tellicherry (Tamil Nadu). Then came the more systematic acts of aggression by the forces of the Provincial Armed Constabulary(PAC) in Uttar Pradesh and policemen in other states in the seventies and eighties — Bhiwandi, Jalgaon (Maharashtra) in 1970, Meerut, Moradabad, Aligarh (UP) in the early eighties, New Delhi in 1984, Meerut, Maliana-Hashimpura (UP) in 1987 and Bhagalpur (Bihar) in 1989. More recently, the inherent bias in the administration and the police force has played itself out through virtual pogroms like those witnessed in Bombay and Coimbatore.

The saga of state, specifically police, complicity and connivance peaked during the December 1992-January 1993 violence in Bombay that swiftly turned from a riot to an unmitigated pogrom against the Muslim minority. This writer tapped police wireless messages during January 1993 which showed the deep-rooted anti-minority hatred that guided the actions of a large section of the Bombay police force. (See box). But despite the findings by over two dozen inquiry commissions appointed to investigate communal riots over the last few decades, none have resulted in prompt criminal prosecutions of those guilty. Given the status, in law, of these commission reports, there is nothing to compel the executive to make the findings public or act on their recommendations. On the contrary, barring exceptions, the Indian executive and administration appears elusive in facing up to the whole question of an anti-minority bias within its administration and law and order machinery.

“Only eight years after the anti-Sikh pogrom in the country’s capital, was any action even initiated against the indicted police officers. Prior to the end of 1991 some of them were even promoted to higher posts.” (Former Union home secretary from 1991-1993, Madhav Godbole, in his autobiography, Unfinished Innings).

Though tragically delayed, two judgements delivered by justices Anil Dev Singh of the Delhi High Court, on July 5, 1996 and by additional sessions judge S.N.Dhingra on August 27, 1996 are path-breakers in relief granted to victims of communal riots because they granted Rs.2 lakh in compensation to Sikh widows and other survivors of the Delhi killings. The court ruled that the state had failed in its prime duty to protect lives guaranteed to every citizen under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

‘We have faith in the government and hope it will bring culprits to book. If that does not happen, things will go beyond our control. Right now, we have given strict orders that violence should not be resorted to’.

-- S.A. Basha, 49, founder-president of the Al Umma, in an interview to the week in early December, soon after the Coimbatore riots. Al Umma was banned immediately after the bomb blasts on February 14 and Basha detained under National Security Act.

Only six years after the 1989 Bhagalpur brutalities, with the publication of the inquiry commission’s majority report, did the Bihar government issue show cause notice to 36 officials including the DGP, G.P. Dohre who was then zonal DIG of Bhagalpur, the DM Arun Jha and the SP, K.S.Dwivedi. It was in Bhagalpur that Muslims were shot and hurriedly buried in fields and cauliflower planted over the corpses. On August 25, 1995 ten persons were awarded life terms for their complicity in the riots, by the second additional district judge. Ten more cases were pending. Of the 836 FIRs filed in connection with the riots, most were “finalised” (read closed) by the courts. They were re-opened subsequently on the intervention of the Bihar Minorities’ Commission.

The genesis of any communal riot can be traced to the spewing of communal poison through hate speech and propaganda by leaders and outfits belonging to communal organisations. Only later do these culminate into murder, loot and arson. The judiciary, hailed by many as the last bastion of even-handedness and fair play, has also shown itself to fall miserably short of expectations.

Vibhuti N. Rai, Inspector General, Border Security Force, is one of the rare exceptions within the IPS who has been addressing the whole question of bias within the police that increasingly perceives itself as “Hindu”. Through this research work, he has drawn attention to the increasing alienation of the minorities.(see page 18). In a path-breaking interview to Communalism Combat (February 1995) he had boldly stated that “No riot can last for more than 24 hours unless the state wants it to continue.” He spoke to CC again after the recent events at Coimbatore. “The bomb blasts in Bombay after the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the recent bomb blasts in Coimbatore have marked similarities. They not only expose the weakness of the internal security mechanism of the country and the show the desperation of the ISI, but also point to a very dangerous situation.” Not everyone who spoke to CC saw a direct comparison between the ground realities of Bombay 1993 and Coimbatore now. But none disagreed over the abject failure the Indian state to protect its minorities and the inherent lack of a commitment to deliver justice and punish those guilty of communally-motivated acts.

To date, far from learning the long-overdue lessons, the experiences of Bombay show how the bomb blasts became yet another excuse to the Bombay and Maharashtra police to unleash a fresh assault on innocent Muslim families. Instead of identifying individual culprits and bringing them to book, the whole community was sought to be tarred with the same “terrorist” (read anti-national) brush. (Box). A tale of chilling similarity is today unfolding in Coimbatore.

Apart from judicial commissions’ reports and reports of investigations by civil liberties’ groups, the National Police Commission, the National Minorities Commission, the National Human Rights Commission, the National Integration Council and individuals have frequently emphasised that the state needs to swiftly and firmly adopt remedial measures to arrest this growing alienation.

These voices that have been urging legal changes for swift punishment to the guilty, greater representation of minorities within the law and order machinery, punitive action against all those officers found implicated through negligence or complicity and a legal obligation on the state to assume financial responsibility for the victims of communal riots. Quality in-service training to both the IPS cadres and the constabulary is another aspect that is being actively debated, given the widespread penetration of communal ideologies and discourse that have not left Indian policemen immune.

While some like Rai have been arguing for a greater representation of the minorities through a policy of reservations, others have been pitching for the same objective through affirmative action. Sixteen years ago in its sixth report, dated March 1981, the National Police Commission, had commented, “(In) several instances police officers and policemen have shown an unmistakable bias against a particular community while dealing with communal situations.”

It added that the composition of the police is “heavily weighted in favour of the majority community. The composition of the personnel in the police system as a whole should reflect the general mix of communities as they exist in society and thereby command the confidence of different sections so that the system would function impartially without any slant in favour of any community...We.. agree that there is a strong case for encouraging the recruitment of members of the minority community and other weaker sections at various levels in the police force.”

Godbole also agrees: “The composition of the UPPAC in Uttar Pradesh certainly required to be changed so as to make it multi-religious on the lines of the Rapid Action Force under the CRPF. The men of the UPPAC also needed to be re-trained to change their psychological orientation.”

Former Director General of Police (retired), Padma Rosha, has contributed substantively to this ongoing debate and has urged strongly that the state must be held culpable for its failure in governance and begin by compensating the victim who is deprived of a life (through comensation to his family), home or means of livelihood. (Communalism Combat, March ’96). More importantly, Rosha has been suggesting that both the DM and SP of the region in which the violence breaks out should face prompt punitive action for their failure in containing the violence.

The suggestion for legal compensation to all victims of communal riots by the state made recently echoes a 20-old recommendation, Grant of Compensation to the Sufferers of Communal Riots, Report of the central Minorities Commission that has based its findings on the opinion of Justice (retd) H.R.Khanna, in1978-79: “The loss of life and property which occurs as a result of communal disturbances may be considered as being on par with the loss of life and property as a result of railway or aircraft accidents caused by sabotage, and the state should be saddled with the legal liability to pay compensation in such cases also. The desirability of passing specific legislation for the payment of compensation by the State to the victims of communal riots may have to be examined...”

Today, the National Minorities Commission, under the chairmanship for Dr. Tahir Mahmood, has set up a committee to draft just such a piece of legislation that was suggested by the same body two decades ago. This committee has, as its members, Justice (retd) V.M.Tarkunde, eminent jurist, Soli Sorabji and constitutional lawyer, Rajeev Dhavan among others. Its task is to draft the Communal Riots (Prevention and Cure)Bill within three months.

What compounds an already negative situation, is the increasing politicisation of policemen themselves. “If a man in charge of the police force, on retirement, joins the Shiv Sena that is rightly or wrongly perceived as a communal organisation, how can we blame the force below him to be biased?” quips Sahney. The reference is to former commissioner of Bombay, R.D. Tyagi, appointed to the post by the Shiv Sena-BJP regime in Maharashtra. On retirement, Tyagi joined the Sena and proclaimed, “I am Balasaheb’s loyal soldier” in a newspaper interview. He was one of the officers indicted in the People’s Verdict, the report of the Indian People’s Human Rights Tribunal on the Bombay riots authored by two retired judges of the Bombay High Court, Justice H. Suresh and Justice S.M. Daud.

The pre- and post-Ayodhya mobilisation by the BJP and its allied organisations in north India saw many similar instances wherein the non-partisan behaviour of district magistrates and senior police officers came into question post-facto when soon after they resigned, they joined the party and even contested elections on a BJP ticket. [Riots -Illustration Amili Setalvad-]The pre- and post-Ayodhya mobilisation by the BJP and its allied organisations in north India saw many similar instances wherein the non-partisan behaviour of district magistrates and senior police officers came into question post-facto when soon after they resigned, they joined the party and even contested elections on a BJP ticket.K.K. Nayar was the DM of Faizabad who had organised the Ramjanmabhoomi movement in Ayodhya. His association with Hindu communal forces was demonstrated when he quit the service and got elected to the Lok Sabha in 1967 on the Jan Sangh ticket; Devendra Bahadur Rai was the senior SP, Faizabad and in charge of law and order in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992 when the mosque was demolished. He was BJP’s member in the dissolved Lok Sabha from Sultanpur and was its candidate again for the seat; K.M.Pande, now a BJP leader, was the magistrate who had ordered the opening of the mosque’s locks; Justice Agarwal of the Allahabad High Court was the man who had rejected an appeal in court filed against Pande’s order. Agarwal is now with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad.

The doyen of the BSF, K.F. Rustomji sums up well the situation, today, “ We put justice as the first principal of our Constitution, but how many of us believe in it today ? We will pay a heavy price for relegating justice to the far corner. Why cannot we see that impartial justice is meant to prevent individuals or groups from taking the law into their own hands to secure it? Why does communal rioting continue in the land? Why did the Coimbatore bomb blast shatter and kill?

Straightforward questions that demand prompt actions in answer.

Teesta Setalvad

Archived from Communalism Combat, March 1998, Year 5 No. 41, Cover Story

Theme image:

Themes Category:

Strapline:

By failing in its duty to protect the life and property of citizens the state sows the seeds of extremism

Classification: