पुस्तकें

Things That Can and Cannot Be Said

Published Date:

Tuesday 27th December 2016 Asia/Kolkata

Summary:

In bringing objectionable practices and policies to light, whistleblowers break the lawful trust of their bosses in order to better serve their real employers – us. President Barack Obama conveyed the displeasure of an unhappy boss in his initial response to government-contracted techy Edward Snowden’s exposure of uncouth data gathering – spying, by another name, on Americans – under the current and previous administrations. “I don’t think Mr. Snowden is a patriot,” Obama grumbled. “My preference, and I think the American people’s preference, would have been for a lawful, orderly examination of these laws [and] a thoughtful, fact-based debate that would then lead us to a better place.”

This appeal to lawfulness was lawyering in its most pejorative sense. The interpretations of law that informed the spying, or retroactively excused it, came about through secret judgments that robbed the public of just such a debate. In effect, the terms were set in advance by what got left out of the conversation.

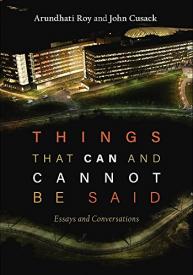

The title of a new collection of essays and dialogues between Booker Prize-winning novelist, activist, and thinker Arundhati Roy and actor John Cusack, Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, speaks to this climate of unbalanced debate and incomplete information. Official forums are plagued by uncertainties, so the real movement toward “a better place” can only come out of less-formal exchanges. Most of the back-and-forths between the writer and the Hollywood celebrity occur in the lead-up to a meeting with Edward Snowden, in late 2014 in Moscow, where they are joined by Vietnam-era intelligence hero, Daniel Ellsberg. Cusack first met Roy at a 2013 talk, in Chicago; transcripts are taken from a series of informal discussions with Roy at his favorite Puerto Rican diner, in New York. By inviting Ellsberg into the exchange, a broader array of historical and economic concerns can be assembled to provide context to Snowden’s ordeal and offer a better understanding of the global imperial juggernaut for which mass surveillance is but one tool in an arsenal of widespread domination.

What can be said is that when Snowden began divulging NSA surveillance activities through Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald and others, Americans like John Cusack immediately publicly condemned the spying. In a June 2013 HuffPo piece, Cusack celebrated “The Snowden Principle,” which affirms the people’s “right to know what the government is doing in their name.” Cusack’s displeasure wasn’t only with how the practices might violate his personal privacy and that of his fellow Americans. The right to know ultimately pointed back to a universal sense of justice, a formal recognition of the Fourth Amendment or the government’s failure to recognize it.

Drawing on her experience growing up and continuing to live in India, Arundhati Roy gives kudos to American self-criticism and “real resistance from within.” Her objection to Snowden is a minor one. She thinks his portrait on the cover of Wired, cradling an American flag, sent the wrong signal to readers outside the States, people in other countries like Afghanistan and Iraq who have experienced the violent repercussions of American military action. To them, the American flag is a symbol of imperial domination and heartache. The leftist politics of Roy’s nonfiction writing aren’t entirely trained on the one global superpower, however, but on how, by following America’s lead, other post-colonial nations like India have adapted in order to be more accommodating to the occupying forces of capitalist exploitation. Her frustrations describe a reluctance to think outside capitalist terms, even by well-intentioned liberals who have marginalized the true discourse of the Left, which “used to be about social justice, equality, liberty and redistribution of wealth.” Instead of fighting for maximum justice, the Left joins up with free-market fundamentalists who use state military power to “liberate” new markets in the name of the minimum, “human rights.” Roy’s sessions with Cusack keep alive the bigger utopian dreams that have lost airtime this century to War on Terror chest-thumping.

Even as the U.S. scales back its troop presence in Middle East terror zones, the dogmatic us-and-them agenda promotes imperial expansion. Roy discusses her time among the forest-dwelling communities in the Indian state of Orissa, the basis of her 2011 expose Walking with the Comrades. Though only some of the guerillas taking refuge in this region could be linked directly with Maoist enemies of the state, the Indian government took full license to attack anyone, including its own citizens, who happened to be occupying unmined hills of bauxite and other valuable materials, clearing out the area for industrial development. Roy’s point is that often in the case of government intelligence, the agenda precedes the fact-finding. In the hills of Orissa, everyone was a Maoist.

As an information gatherer for the Pentagon in the 1960s, a young Daniel Ellsberg was charged with building the case for military action in Vietnam. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s office requested any “atrocity details” that Ellsberg could find committed by Viet Cong. The Rolling Thunder campaign soon followed, touching off eight years of “kill anything that moves” bombardment. Haunted by his involvement in setting the stage, Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, a top secret internal study of the government’s decision making.

On their way to Moscow, Roy and Cusack meet up with Ellsberg in Stockholm, where the Swedish Parliament hosts the Right Livelihood Awards, also known as the “Alternative Nobels,” for which Ellsberg is a laureate. The writer and the actor are late to the ceremony and, like old friends or Muppets, make fun of corporate-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs), from a crowded balcony.

In Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, traveling to see Snowden is a little like waiting for Godot. The non-event clears the way for an empty contemplative space. It also keeps individual personalities and motives at a distance so that a major political theorist like Roy can connect the dots, revealing deeper systemic motives. Surveillance determines policy and silences opposing viewpoints. Saying the right thing – for the cause of justice over complacency – becomes a noble end in itself.

Christopher Wood is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, who now lives on Long Island.

This appeal to lawfulness was lawyering in its most pejorative sense. The interpretations of law that informed the spying, or retroactively excused it, came about through secret judgments that robbed the public of just such a debate. In effect, the terms were set in advance by what got left out of the conversation.

The title of a new collection of essays and dialogues between Booker Prize-winning novelist, activist, and thinker Arundhati Roy and actor John Cusack, Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, speaks to this climate of unbalanced debate and incomplete information. Official forums are plagued by uncertainties, so the real movement toward “a better place” can only come out of less-formal exchanges. Most of the back-and-forths between the writer and the Hollywood celebrity occur in the lead-up to a meeting with Edward Snowden, in late 2014 in Moscow, where they are joined by Vietnam-era intelligence hero, Daniel Ellsberg. Cusack first met Roy at a 2013 talk, in Chicago; transcripts are taken from a series of informal discussions with Roy at his favorite Puerto Rican diner, in New York. By inviting Ellsberg into the exchange, a broader array of historical and economic concerns can be assembled to provide context to Snowden’s ordeal and offer a better understanding of the global imperial juggernaut for which mass surveillance is but one tool in an arsenal of widespread domination.

What can be said is that when Snowden began divulging NSA surveillance activities through Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald and others, Americans like John Cusack immediately publicly condemned the spying. In a June 2013 HuffPo piece, Cusack celebrated “The Snowden Principle,” which affirms the people’s “right to know what the government is doing in their name.” Cusack’s displeasure wasn’t only with how the practices might violate his personal privacy and that of his fellow Americans. The right to know ultimately pointed back to a universal sense of justice, a formal recognition of the Fourth Amendment or the government’s failure to recognize it.

Drawing on her experience growing up and continuing to live in India, Arundhati Roy gives kudos to American self-criticism and “real resistance from within.” Her objection to Snowden is a minor one. She thinks his portrait on the cover of Wired, cradling an American flag, sent the wrong signal to readers outside the States, people in other countries like Afghanistan and Iraq who have experienced the violent repercussions of American military action. To them, the American flag is a symbol of imperial domination and heartache. The leftist politics of Roy’s nonfiction writing aren’t entirely trained on the one global superpower, however, but on how, by following America’s lead, other post-colonial nations like India have adapted in order to be more accommodating to the occupying forces of capitalist exploitation. Her frustrations describe a reluctance to think outside capitalist terms, even by well-intentioned liberals who have marginalized the true discourse of the Left, which “used to be about social justice, equality, liberty and redistribution of wealth.” Instead of fighting for maximum justice, the Left joins up with free-market fundamentalists who use state military power to “liberate” new markets in the name of the minimum, “human rights.” Roy’s sessions with Cusack keep alive the bigger utopian dreams that have lost airtime this century to War on Terror chest-thumping.

Even as the U.S. scales back its troop presence in Middle East terror zones, the dogmatic us-and-them agenda promotes imperial expansion. Roy discusses her time among the forest-dwelling communities in the Indian state of Orissa, the basis of her 2011 expose Walking with the Comrades. Though only some of the guerillas taking refuge in this region could be linked directly with Maoist enemies of the state, the Indian government took full license to attack anyone, including its own citizens, who happened to be occupying unmined hills of bauxite and other valuable materials, clearing out the area for industrial development. Roy’s point is that often in the case of government intelligence, the agenda precedes the fact-finding. In the hills of Orissa, everyone was a Maoist.

As an information gatherer for the Pentagon in the 1960s, a young Daniel Ellsberg was charged with building the case for military action in Vietnam. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s office requested any “atrocity details” that Ellsberg could find committed by Viet Cong. The Rolling Thunder campaign soon followed, touching off eight years of “kill anything that moves” bombardment. Haunted by his involvement in setting the stage, Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, a top secret internal study of the government’s decision making.

On their way to Moscow, Roy and Cusack meet up with Ellsberg in Stockholm, where the Swedish Parliament hosts the Right Livelihood Awards, also known as the “Alternative Nobels,” for which Ellsberg is a laureate. The writer and the actor are late to the ceremony and, like old friends or Muppets, make fun of corporate-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs), from a crowded balcony.

AR: Embrace the resistance, seize it, fund it.These two and Ellsberg then fly to Moscow to meet with Snowden at the Ritz-Carlton, adjacent to the Kremlin. Transcripts from the conference are not provided, but Cusack suggests “maybe one day the NSA will give us the minutes of our meeting.” Over two days, Cusack reports, Snowden and Ellsberg share intimate conversations about their careers and politics. The impact on Ellsberg reduces the 83-year-old to tears in his hotel room.

JC: Domesticate it . . .

AR: Make it depend on you. Turn it into an art project or a product of some kind. The minute what you think of as radical becomes an institutionalized, funded operation, you’re in some trouble. And it’s cleverly done. It’s not all bad . . . some are doing genuinely good work.

JC: Like the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) . . .

AR: They have money from the Ford Foundation, right? But they do excellent work. You can’t fault people for the work they’re doing, taken individually.

JC: People want to do something good, something useful . . .

In Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, traveling to see Snowden is a little like waiting for Godot. The non-event clears the way for an empty contemplative space. It also keeps individual personalities and motives at a distance so that a major political theorist like Roy can connect the dots, revealing deeper systemic motives. Surveillance determines policy and silences opposing viewpoints. Saying the right thing – for the cause of justice over complacency – becomes a noble end in itself.

Christopher Wood is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, who now lives on Long Island.