इंटरव्यू

The role of a lifetime

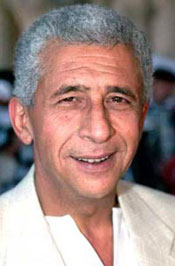

Actor Naseeruddin Shah discusses the vagaries of religion, the Bollywood ethos and his future in cinema

Q: What was the reaction in Pakistan to Khuda Kay Liye? Did you visit Pakistan after the movie was released?

A: The reaction was absolutely unbelievable. In Pakistan the theatres are very tacky, badly equipped, there is no air conditioning and rats run across your feet. They are like those old theatres that we still have in towns like Aligarh and Meerut. There are no multiplexes, no places where a person could go with the family. Yet this movie ran in theatres to packed houses for over 100 days. It was released at the same time the Lal Masjid incident occurred. Whether that was engineered or not, I don’t know.

Now I think the government was behind it – backing it – which is why it overrode all objections made by the madrassas. The director and some of the actors received threats. Therefore I credit them doubly for having the courage to do the film. I was recognised everywhere I went in Pakistan. People would hug me and thank me for making this film. It was more than mere sentiment and therefore it appealed to people.

The film was well researched. I consider it to be the most significant film I have ever made despite the brevity of the role. Initially, I turned the film down. I turned it down because I had seen Pakistani movies. But the scenes that were narrated to me were hair-raising and these are exactly the things that matter to me.

I did a thorough study of Islam (for the role of a Muslim cleric). I learnt the Koran in my childhood because I was made to. We still don’t feel the need to tell our children the meaning of what we read. We just memorise it like drill and recite it when there is a need to. That’s all we are taught. This must end. Muslim children must be taught what it means. There I was, a five-year-old child, told by the maulvi that ‘every kafir will go to hell, every Muslim will go to hell; when you grow up you must grow your beard and wear a pyjama’ and so on.

The movie reached more people than my other movies – such as Nishant – did. Nishant was also human-centric. There is a worldwide obsession with Islam. There is a hatred for Islam, which is unreasonable, biased and unfair. What bothers me most of all as a Muslim however is this seemingly rising awareness in youngsters of their identity as Muslims. The rising awareness doesn’t bother me as much as their misdirection. It is almost as if they are vigorously trying to compensate for the shortcomings in their own lives by living in the hereafter.

It seems to be happening a lot among Muslims. You see much more of an assertion of Muslim identity over the last 10 years, you hear many more salaam walekums than you heard earlier, you see many more men visibly sporting beards during namaz. I suppose the same thing is happening among the Hindus.

I’m really curious – particularly among the young Muslim men who are turning devout – whether there is in fact a deep study of Islam taking place or is it just the rewards of what awaits believers after death that is attracting them. These are the kinds of things that worry me. I think I can say this without offending Hindus or Muslims, that you need more awareness of the world and you must learn to interpret the vision according to the needs of the day.

It is in fact very puzzling as to why this is happening. If you’ve travelled to the US and have been hassled by immigration because of your name then I can also sort of understand that angle.

Q: Do you think that – at least in India or perhaps the subcontinent – we are ignoring the sane voice that understands the worldliness essential for living and also understanding religion?

A: Nobody speaks up against this absurd member of parliament who offered a crore of rupees for the head of the Danish cartoonist. Where did this man get a crore of rupees is a question nobody has asked. That seems of no importance. He has offended our sentiments and so he must die. The alarming thing is that you find so many people willing to do this. It can be downright frivolous for someone like me to stand up and talk against this person. So what are we to do if we are not activists nor are we soldiers?

I think the start has to be made in our own lives in a small sort of way. I think too many people obsessed with social change tend to reach too far, too quickly. I feel that if I’m rearing my children with an awareness of each religion as I understand it and not classifying them as Hindu or Muslim it is a progressive step. I’m leaving them free to choose the religion that suits them; that serves their purposes because that’s what religion is supposed to do.

Sweeping it under the carpet and apathy are old characteristics of our nation.

Q: This is obviously a very difficult position to maintain, given the circumstances. Does that sometimes frighten you, the sheer magnitude?

A: It terrifies me because I don’t know when it is going to end. It seems that religion, which was perhaps created to unify, is serving the opposite purpose. At the same time what also terrifies me is if my children, 20 years from now, are confronted by a mob that wants to know their religion. What are they going to say?

But I take solace in the fact that they will not be parochial and hide under the shelter of false hopes, of "I belong to this community and so I am safe".

The narrowing interpretation of Islam that is taking place is what really terrifies me because it is giving Islam a worse name than it already has. Too many of our so-called spokesmen are aggravating the issue. This has become clearer over the past few years.

Q: Professionally, do you feel that you are currently at the richest stage of your life as an actor or do you feel that you have done terrific work earlier and now it is no longer the same?

A: The environment is more conducive to doing better work. I don’t feel like I’ve done whatever I am capable of. I don’t look back on my past work and think it’s fantastic. There’s a lot of it I don’t like in fact and yes, I would say the answer to that is yes. Because the craft of the filmmaker has grown over the last 30 years their consciousness has grown too.

It is no longer fashionable to make movies on exploited peasants about whom we know nothing. The situation is much more alive now because filmmakers are attempting to make films on subjects they know about, subjects they’ve seen before. I’ve always believed that you cannot calculate the success of a movie before it is made; it should be made with conviction.

There seems to be lot more courage in today’s filmmakers. You have, apart from a film like Khuda Kay Liye, a film like A Wednesday and Nandita (Das)’s film Firaaq based on Godhra, which is extremely hard-hitting and extremely well made and which I am very proud of. Even a movie like Parzania, which it still takes an NRI to make. Still, he is an Indian who feels for the situation.

You have directors like Anurag Basu, Rituparno Ghosh and Neeraj Pandey – these are the people I have hope for and these are the people who have got their craft down pat and have a socially aware mind. These are people who want to tackle the real issues and not make fancy movies.

Among the filmmakers of the 1970s there was a bit of posturing and it showed in the way their commitment disappeared as soon as greener pastures arrived. As an actor too I feel it is richer ground for me. I may not be getting great roles to display my abilities as I did in the past but that doesn’t trouble me because to prove my worth as an actor is not of any concern to me any more. To participate in a project which I feel is significant is what attracts me.

Q: You were a very strong critic of the cinema that existed even though you were a part of the industry…

A: I was a critic of the quality of work, not a critic of the type of cinema. I’ve been misinterpreted greatly. In fact, I’ve even been quoted somewhere as saying that I hate good cinema. Why would I be idiotic enough to say that? My complaint was against the level of commitment of those filmmakers and the stagnation of their craft. That’s what I was angry about and that’s what turned me against them in the sense that I don’t want to work with some of those filmmakers any more.

But there are plenty of youngsters who I’m still working with, more first-time filmmakers than established ones. So perhaps it is my maturing as an actor and my realising that acting is not an end in itself. You don’t act to show off your acting, you act because you’ve put your abilities at the service of somebody who helps to make a statement. As an actor you are never making your own statement, you are a mouthpiece for others.

Q: How has the Hindi film industry, in your opinion, progressed? Has it got better?

A: It has become more self-congratulatory. It believes the world is sitting up and taking notice. In a way the world is sitting up and taking notice only because of the multicoloured mithai. I don’t know if there is true enjoyment of these movies or whether they are considered to be anything significant. For the NRIs it is a great link to home – you get together and eat your samosas and talk in Hindi and you cry. It is a mirage to say that Bollywood cinema has gained acceptance worldwide. As far as the film industry is concerned, it is exactly where it was; their concerns are still with making huge amounts of money and satisfying the self-agenda.

Q: It must be a business kind of pursuit when the amount of money involved is so great and so many lives are depending on it. Is this because somebody is coughing up money and you need a return on the investment?

A: Our cinema has modelled itself on the Hollywood of the 1940s and 1950s, with one huge difference. We are still trying to make those kinds of musicals, those musical numbers, those basic stories – exchange babies, boy meets girl or rich boy-poor girl – We are still making those kinds of stories without the excellence of the old music.

You see a film like Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and it still delights me even though it was made in the 1950s. You see the Hindi version of it and it turns your stomach. The big difference between Hollywood (at that time) and our industry is that even though the producers of those days loved money and multiplying their investments they also loved movies. And even at that time there were socially aware movies that came out once in a while. Why can’t we do that?

I understand the love for money and I understand you want to get your investment back and see that your family doesn’t lose its standard of living and so on. What is preventing you from searching your conscience, from wondering what kind of movie one should really be making with the kind of facilities at our disposal?

It is obviously sufficient for a person in the position of Rakesh Roshan or Subhash Ghai to continue churning out those Hollywood imitations so that they can multiply their investments. There is a superficial nod towards a technical finish. I think it is just the whole concept of Hindi movies which is so shallow that a person who thrives on that kind of life, for whom it is a part of his bloodstream, I don’t think is capable of these kinds of thoughts. When he is asked to invest one zillionth of his fortune in a film that will state something of importance he will not do it. It is a lamentable situation.

Q: The audience that laps it up…

A: They will always lap it up. There are umpteen movies, with stars and the formulae, which the audience never really went to see. The audience is not taken into consideration. The filmmakers say they cater to the audience but the films are not made for the audience. They are made to multiply their own investments. And now you can recover and make a healthy profit in the first week itself. So all you need to do is to con the audience to get in there on Friday, Saturday and Sunday and you are sitting on a gold mine. The days of 50-week runs are gone, even the desire to make a good film is gone. You just have some slick stuff that will pull the audience in on the first three days and your job is done. I think they are heading down a dark end.

Q: You did make a valiant attempt to become director…

A: The film was not accepted. It was my film producer who completely lost faith while it was being made and then refused to do anything to help it get noticed so it sank without a trace. I don’t feel broken up about it because it would have been just one little straw in the wind. At least it was made. But I do feel disappointed that I couldn’t make a better film.

I feel disappointed that the audience did not respond to it. I don’t feel shattered and discouraged at the end of the day. I hope to attempt another one at some point. That film was attempted, as it was the kind of subject or script that states something or coincides with my beliefs. I had absolutely no hesitation in doing it. There are many things that trouble me, that trouble any man: The lack of consideration towards the common man and his complete facelessness.

I have taken my standing as an actor too lightly. I have participated in movies that I felt were making significant statements but it has not been a consuming passion. I was also at a point where I was struggling to become a popular actor. I have been through it all and survived.

At this moment what is of prime importance to me is to participate in movies that state something and follow ideas that it was not possible for me to do before. And hence my choice of films like Khuda Kay Liye. I’m not someone who believes in making political statements in an individual capacity. I am not interested in politics and politicians just turn me off. Nor have I believed in wearing my heart on my sleeve like many actors do. I didn’t feel the need to do it all these years and have not done it. I finally feel the need. I am approaching what could be said is the last innings of my career.

(Ayaz Memon is editor-at-large of the DNA. Excerpted from an interview posted on www.dnaindia.com on August 29, 2008.)

Courtesy: www.dnaindia.com

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2008 Year 15 No.134, Cover Story 4