IMAGE STORY

The Dispossessed, Citizen Nagar, Gujarat

-

“We may be survivors, but you are spectators. You watched. You felt in your skin. So it is our story we preserve as ours.”

“Riots earlier had a sense of repair, of reciprocity, of apology at least in their aftermath. This riot lacked apology, it sought to root out a community.”Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“Transit camps are rarely temporary. They begin as an act of desperation, created as a fragment by some desperate and sustained by a few NGOs. As funds run out, even the NGOs leave. Located miles away from the main road, these camps are soon forgotten.

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“What connects that camps to reality is corruption; the corruption of the municipal corporation and the violence of the goons who disallow any act of progress, any little repair or improvement in case they lose control of their turf. The names of the areas bring out irony of disaster relief. These areas are named in hope, or may be cynically, as Ekta Nagar invoking unity, Citizen Nagar, summoning entitlement.”

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

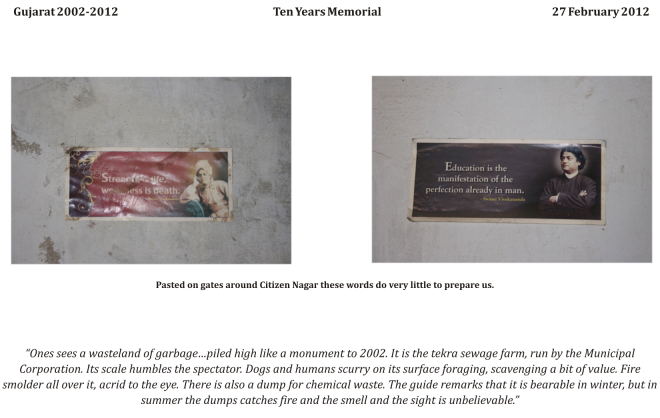

“Ten years, and almost nothing has happened in these areas. Only children are proud of school, and list out their classes as honor lists. May be education is a way out.”

On Citizen Nagar. “Ones sees a wasteland of garbage…piled high like a monument to 2002. It is the tekra sewage farm, run by the Municipal Corporation. Its scale humbles the spectator. Dogs and humans scurry on its surface foraging, scavenging a bit of value. Fire smolder all over it, acrid to the eye. There is also a dump for chemical waste. The guide remarks that it is bearable in winter, but in summer the dumps catches fire and the smell and the sight is unbelievable.”Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“The visitor feels like an archaeologist at a monument, a memorial to waste, junk, and garbage smoldering like the people. Bulldozers come in everyday and vomit their new pile of indifference while kites keep a vigilant eye. It is almost as if the shit of the city is piled on the survivor, saying this is what we think of you.”

The size and the scale of the dump leave you in awe. It is like an inverted heritage site selected by a surreal UNESCO to mark the violence and carnage of 2002.”Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“One realizes that for many, waiting has made them sluggish; it has created a form of dependency, a sense of sloth as the magic of the state and the promises of politicians have failed to work. Life becomes hopeless, a habit, where each day repeats its arid self. The heroism of subsistence and survival has few storytellers”.

“There is something about the alchemy of the camps, the unstated pain and suffering which asks question of those who visit it. Is one a spectator? Is a spectator a consumer of disasters? A voyeur of the new histories of pain and suffering?”Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“The ethnography of camps demands a range of reflections. One has to admit that merely visiting them, sitting with survivors, walking around is not living in them. To understand that, one needs to make a leap of imagination; to understand life worlds devastated by violence.

Once is faced with uneasy questions: Is waiting for help or even justice a form of addiction? Does waiting corrupt the giver and the receiver? How does a society where so many ordinary people were murdered, raped and looted, live so easily with it self? One sees few traces of guilt. In fact, one sees explanations of the act as if history has at last redeemed itself; one hears the litany of the same arguing that Godhra validated their violence. Once feels that a society has canned the event an moved on blissfully. Gujarat, as a society, has washed its memories away.”Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“Rafiq Sahib who has worked in many areas added that the pattern of riots almost behaves like the waves of a business cycle. A riot emerges and flattens out Muslim livelihood and business. The Muslims rebuild again, and as soon as that grows; another riot emerges to flatten it out. Rafiq added, “Look at the years 47,69,81,92,2002; each flattened the economic foundation of Muslim livelihood. I do not know whether they are correlations or causations but it is time we read the patterns of riots.”

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“Past and present merge in their narrative. Things are better. The only real complaint is the stagnating water in the rains and the waste disposal. Yet there is also the everydayness of trauma refuses to go away. “My child sleeps with me, walking up again and again screaming. The violence never goes away,” says Sakina Bibi.

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“The women gather to review the past. They explain that not everyone was violent Parmars and Rajputs in their areas were not. Who they feared were Adivasis and the Bajrang Dal. Their stories become a chorus as they echo a sequence of how they fled, abandoning their houses, hiding in the fields, watching the looting, and waiting for help. No one came to help. In fact, police stopped people from entering the area, creating a cordon for violence.”

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah -

“Memory cannot compete with files, as files only recognize official memory. Pain and trauma do not quality till they are medicalised.”

Photo Credits:Binita Desai, Chinar Shah